The Link Between Mouth Breathing, Airway Obstruction, Sleep Fragmentation, and NADPH Metabolism

A clinical and biochemical framework for understanding oxidative stress, fatigue, and neurocognitive decline

Emerging evidence supports a clinically important connection between upper airway obstruction, mouth breathing, and sleep fragmentation—not just as “sleep issues,” but as upstream drivers of NADPH dysregulation, oxidative injury, mitochondrial stress, and multi-system inflammation.

Why NADPH Matters in Airway and Sleep Disorders

NADPH (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate) is a critical reducing cofactor that supports:

• Glutathione recycling (via glutathione reductase)

• Thioredoxin-based antioxidant defence

• Nitric oxide synthesis (NOS enzymes require NADPH as an electron donor)

• Mitochondrial redox stability and cellular resilience

• Detoxification capacity and inflammatory control

When airway obstruction and disordered sleep repeatedly increase oxidative demand, NADPH availability becomes a limiting factor. The result is not only oxidative stress, but impaired capacity to recover from oxidative stress—a key distinction in chronic disease progression.

Obstructive Sleep Apnoea: Intermittent Hypoxia as a Redox Injury Pattern

Intermittent Hypoxia Is Not “Low Oxygen”—It’s Reperfusion Injury

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) causes repeated airway collapse with cycles of hypoxia followed by reoxygenation. Biochemically, this resembles ischemia–reperfusion injury, a well-known trigger for systemic oxidative stress.

This pattern is a major upstream driver of NADPH disruption because reoxygenation phases can generate large ROS bursts that must be neutralized by NADPH-dependent antioxidant systems—at the same time that NADPH oxidases may be actively consuming NADPH to generate superoxide.

NADPH Oxidase Is a Central Mediator

A core mechanistic finding across models is that intermittent hypoxia upregulates NADPH oxidase activity, increasing superoxide generation. Subunits such as p47phox and p22phox appear repeatedly in experimental and clinical observations, reflecting increased assembly and activation of the enzyme complex.

Clinically, this matters because NADPH oxidase does not merely “create oxidative stress.” It consumes the same cofactor (NADPH) needed to regenerate antioxidant capacity—especially glutathione. This makes the oxidative burden harder to resolve over time.

NOX2 and Organ-Specific Injury

NOX2 and Organ-Specific Injury

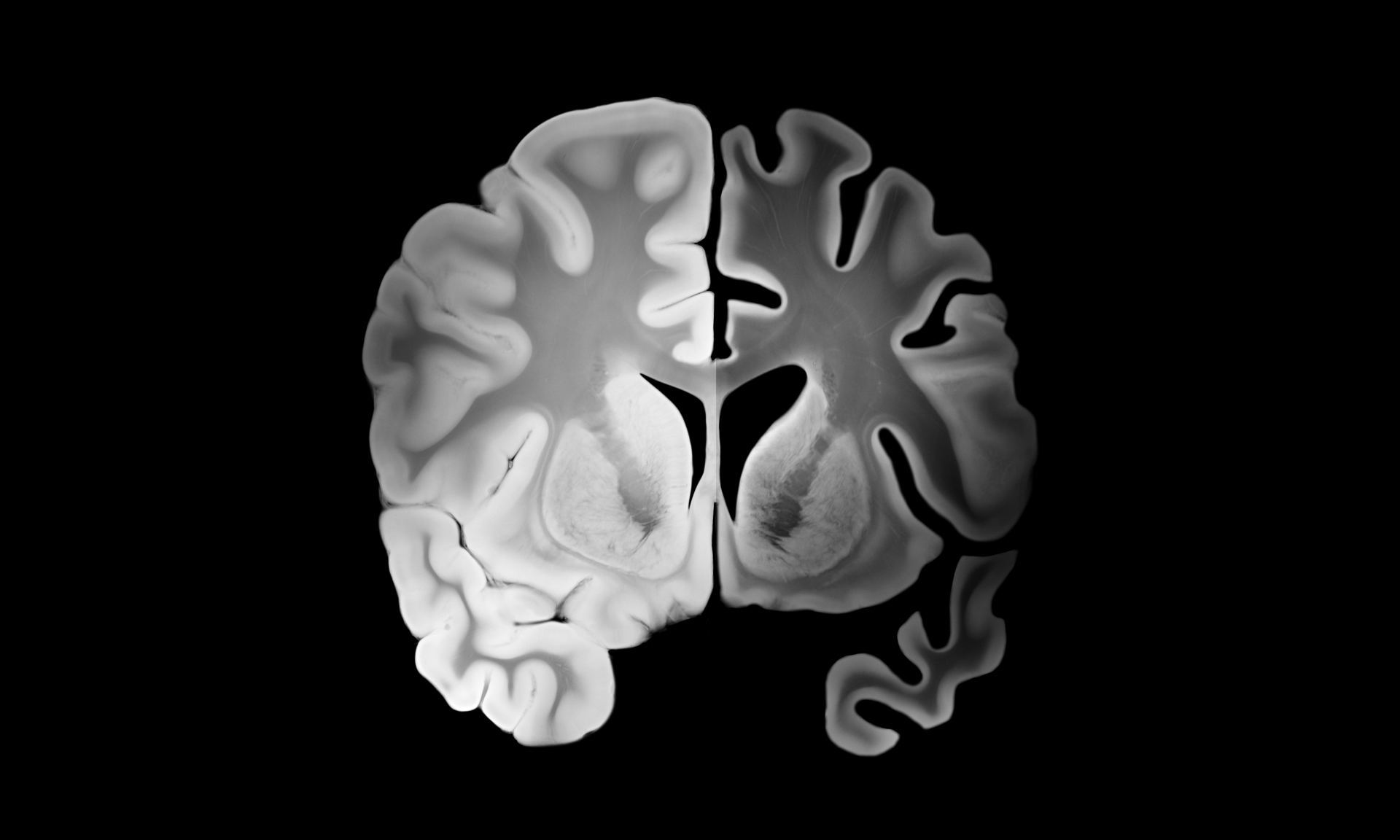

While NADPH oxidases exist as multiple isoforms, NOX2 is frequently implicated in OSA-related oxidative injury across systems, including the brain and cardiovascular tissues. Patterns of oxidative stress can be organ-specific and duration-dependent, but NOX2 repeatedly emerges as a key contributor to:

• neurocognitive injury (hippocampal and cortical vulnerability)

• vascular dysfunction and hypertension

• cardiac remodelling

• pulmonary vascular changes in long-term intermittent hypoxia

Glutathione Collapse: When NADPH Demand Exceeds Supply

OSA Is Associated With Reduced Antioxidant Capacity

Clinical studies consistently show that OSA patients often exhibit lower antioxidant capacity, despite (and partly because of) increased oxidative signalling. NADPH oxidase activation, lipid peroxidation, and ROS burden rise while the body’s capacity to buffer these effects declines.

The Vicious Cycle: NADPH Oxidase vs Glutathione Recycling

The mechanistic trap looks like this:

1. Intermittent hypoxia activates NADPH oxidase → increased superoxide generation

2. NADPH is consumed during oxidase activity

3.Reoxygenation increases ROS load that must be detoxified

4. Detoxification depends on glutathione, but glutathione recycling requires NADPH

5. The system spirals: more oxidative stress + less recovery capacity

This is why some patients experience progressive symptoms despite “only” having sleep-disordered breathing: their redox system is being drained from both ends.

Sleep Fragmentation: Cognitive Decline Without Hypoxia

Sleep Fragmentation Activates NADPH Oxidase in the Brain

One of the most clinically relevant findings is that sleep fragmentation alone, even independent of hypoxia, can drive NADPH oxidase activation and neurocognitive impairment.

Animal research using models lacking key NADPH oxidase activity demonstrates strong neuroprotection against sleep fragmentation-induced deficits—implicating NADPH oxidase as a direct mediator of:

• memory impairment

• depressive-like behaviour

• anxiety patterns

• reduced cognitive performance on spatial tasks

This aligns with clinical reality: many patients with disturbed sleep (even without profound desaturation) present with brain fog, mood instability, and reduced executive function.

Hippocampal Vulnerability

The hippocampus is highly sensitive to oxidative stress. When sleep fragmentation increases NADPH oxidase activity in cortical and hippocampal tissue, spatial learning and memory performance deteriorate—reflecting a biochemical injury pattern, not simply “being tired.”

Mitochondrial Dysfunction: The Energy Cost of Disrupted Sleep

Sleep disruption is strongly linked to mitochondrial stress, including:

• mitochondrial fragmentation

• altered mitophagy

• increased mitochondria–ER stress interactions

• impaired respiratory chain function

• amplified ROS generation

NADPH oxidase activity and mitochondrial dysfunction can intensify each other through feedback loops: oxidative stress damages mitochondrial function, and impaired mitochondria generate more ROS under stress.

Clinically, this is one reason chronic sleep disruption can evolve into a broader syndrome of fatigue, poor recovery, and systemic inflammation—especially in metabolically vulnerable individuals.

Mouth Breathing: Loss of Nasal Nitric Oxide and “Silent” Hypoxia

Nasal Nitric Oxide Is a NADPH-Dependent Defence System

The nasal cavity produces significant nitric oxide (NO), and NO synthesis via NOS enzymes is NADPH-dependent. Nasal NO contributes to:

• improved pulmonary perfusion and oxygen uptake

• antimicrobial and antiviral activity

• mucociliary clearance

• improved airway tone and oxygen delivery dynamics

When nasal breathing is replaced by chronic mouth breathing, a key protective system is removed—not only a mechanical filter, but a biochemical defence layer.

Mouth Breathing Can Create Tissue Hypoxia Even With “Normal Oxygen”

Mouth breathing often shifts ventilation patterns toward rapid, shallow breathing with excessive CO₂ loss. This can impair oxygen delivery at the tissue level through Bohr effect suppression—meaning oxygen may not be released efficiently from haemoglobin despite adequate saturation.

The result is a form of chronic cellular hypoxia that can stabilize hypoxia signalling pathways and increase oxidative and inflammatory stress—again increasing NADPH demand.

Adenoid Hypertrophy, Rhinitis, and ER Stress: Inflammation That Drives NOX Activation

Upper airway obstruction is often driven by inflammatory causes such as:

• adenoid hypertrophy

• allergic rhinitis

• chronic nasal inflammation

These conditions can generate ER stress and unfolded protein response signalling, which can amplify oxidative pathways and upregulate NADPH oxidase activity—especially NOX2—tightening the loop:

chronic inflammation → ER stress → NOX upregulation → ROS → glutathione depletion → impaired redox recovery → more inflammation

This is a clinically useful framework because it shows why “just treating symptoms” may fail unless airway mechanics and inflammatory drivers are addressed together.

Craniofacial Structure and the Self-Perpetuating Loop

Airway Shape Determines OSA Risk

Craniofacial architecture strongly influences airway patency. Structural factors that narrow the airway increase the likelihood of collapse during sleep as muscle tone drops.

Mouth Breathing Also Worsens Craniofacial Development

The relationship is bidirectional. Narrow airway anatomy promotes mouth breathing, and mouth breathing in childhood can shape development in ways that further narrow the airway (high palate, altered jaw growth patterns, malocclusion, low tongue posture), reinforcing future sleep-disordered breathing.

This is how airway dysfunction becomes “programmed” into structure over time.

Mitochondrial Disease: A High-Risk Intersection With Sleep-Disordered Breathing

Children and adults with mitochondrial disorders may be uniquely vulnerable because:

• baseline energy production is already compromised

• NADPH production capacity may be reduced in specific mitochondrial defects

• intermittent hypoxia and sleep fragmentation add oxidative pressure

• redox instability worsens mitochondrial function further

In these patients, sleep-disordered breathing is not a minor comorbidity—it can act as an accelerant of metabolic decline.

An Integrated Model: The Airway–NADPH–Mitochondrial Cascade

A practical way to conceptualize the full pathway:

1. Airway compromise (structural + inflammatory)

2. Mouth breathing + nasal NO loss + altered CO₂ physiology

3. Sleep fragmentation and/or intermittent hypoxia

4. NADPH oxidase upregulation (often NOX2)

5. Glutathione depletion + reduced antioxidant capacity

6. Mitochondrial dysfunction + ATP deficit

7. Multi-system consequences: fatigue, cognitive decline, immune dysfunction, cardiometabolic disease

8. Self-perpetuating loop: inflammation and poor sleep worsen airway function and recovery capacity

Conclusion

Mouth breathing, nasal obstruction, intermittent hypoxia, and sleep fragmentation are not isolated lifestyle issues. They can drive a coherent biochemical sequence centered on NADPH oxidase activation, glutathione depletion, and mitochondrial dysfunction, producing systemic oxidative stress and multi-organ consequences.

The clinical significance is that these processes are often treatable and interruptible, especially when identified early. Addressing airway patency and sleep stability is not only respiratory medicine—it is metabolic medicine, redox medicine, and neurological risk reduction.