NADPH: A Deep Dive into Molecular Structure, Biochemistry, and Clinical Relevance

Dr Scott Wustenberg DC, FACNEM | M.Sc. Nutritional Medicine (Distinction) | B.Sc. Chiropractic | B.Sc. Physiology/BiochemistryEmail for communication: neo@advancerehab.com.au

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) is a central biochemical “currency” of reducing power. It underpins anabolic metabolism, antioxidant defence, detoxification capacity, immune function, and multiple signalling pathways that shape cardiometabolic, neurodegenerative, and cancer biology. While it is often discussed alongside NAD⁺/NADH, NADPH’s primary role is not energy extraction—it is cellular construction and protection.

What NADPH Is and Why It Matters

NADPH is a critical redox cofactor with the chemical formula C₂₁ H₂₈ N₇ O₁₇P₃ and molecular weight 743.4 Da. It exists in two interconvertible forms:

• NADP⁺ (oxidized)

• NADPH (reduced)

Structurally, NADPH is nearly identical to NAD, differing by a single phosphate group attached to the 2′-hydroxyl of the adenosine ribose. This subtle difference produces a major functional divide:

• NAD/NADH tends to drive catabolic energy production

• NADP/NADPH supports anabolic biosynthesis and cellular defence

NADPH has a standard redox potential around -320 mV, making it a strong reducing agent. In practical terms, this means NADPH is biochemically positioned to donate electrons and drive reactions that require reducing power—particularly those involved in building molecules and buffering oxidative stress.

NADPH Production Pathways

Cells maintain NADPH through multiple sources. The relative contribution varies by tissue type, metabolic state, and compartment (cytosol vs mitochondria).

Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP): The Primary Source

In animals and non-photosynthetic organisms, the oxidative phase of the pentose phosphate pathway is the major NADPH generator. It produces two NADPH molecules per glucose-6-phosphate routed through the oxidative arm:

1. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) catalyses the rate-limiting step, producing NADPH.

2. 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (PGD) generates a second NADPH and releases CO₂.

G6PD as a Metabolic Sensor

G6PD activity responds to the NADPH/NADP⁺ ratio:

• High NADPH → feedback inhibition → PPP slows

• Rising NADP⁺ (higher demand) → inhibition relieved → PPP accelerates

This design allows the cell to scale NADPH production to match requirements such as lipid synthesis or oxidative stress handling.

Alternative NADPH-Generating Pathways

Beyond PPP, several routes contribute to NADPH pools:

Malic Enzyme 1 (ME1) (cytosolic): malate → pyruvate + CO₂ + NADPH Notably active in adipose tissue, supporting fatty acid synthesis.

Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) (cytosolic): isocitrate → α-ketoglutarate + NADPH Contributes significantly in certain contexts.

Folate-mediated NADPH production: one-carbon metabolism can generate NADPH (including mitochondrial relevance).

Nicotinamide Nucleotide Transhydrogenase (NNT) (mitochondrial): couples NADH → NADPH conversion to proton translocation, supporting mitochondrial NADPH.

Photosynthetic organisms: generate NADPH via ferredoxin–NADP⁺ reductase in photosynthetic electron transport (relevant as a conceptual analogue, even if not human physiology).

Core Anabolic Functions of NADPH

NADPH is fundamentally an “anabolic enabler”—it powers reductive biosynthesis.

Lipid Biosynthesis

NADPH is essential for de novo fatty acid synthesis. The fatty acid synthase complex consumes NADPH during reduction steps in each elongation cycle, requiring two NADPH for each two-carbon addition.

Beyond fatty acids, NADPH is also essential for:

• Cholesterol biosynthesis

• Steroid hormone production

• Phospholipid synthesis

Steroidogenic tissues (e.g., adrenal cortex) rely heavily on PPP-derived NADPH, with enzymatic activity often localized near smooth endoplasmic reticulum where steroidogenesis occurs. The first and rate-limiting step of steroid hormone production is NADPH-dependent.

Nucleotide Synthesis

NADPH supports nucleotide biosynthesis indirectly by maintaining reduced thioredoxin/glutaredoxin systems required for ribonucleotide reductase, which converts ribonucleotides into deoxyribonucleotides for DNA synthesis.

• NADPH for reducing power

This dual supply is one reason proliferating cells depend heavily on PPP activity.

Detoxification and Drug Metabolism

The cytochrome P450 (CYP) system depends on NADPH as the electron donor (via NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase, with FAD/FMN intermediates). This electron transfer enables oxidation/hydroxylation reactions essential for metabolizing:

• pharmaceuticals

• environmental toxins

• carcinogens

Antioxidant Defence and Redox Resilience

NADPH is a cornerstone of cellular antioxidant defence because it sustains the reduced state of key antioxidant systems.

Glutathione System

NADPH is required for glutathione reductase to regenerate GSH from GSSG. This directly supports ROS neutralization. When NADPH drops, the GSH/GSSG ratio declines, leaving cells vulnerable to oxidative injury.

The clinical significance is straightforward: NADPH availability often determines how well a cell can respond to oxidative stress.

Thioredoxin System

NADPH also powers thioredoxin reductase, regenerating reduced thioredoxin which then:

• reduces protein disulfides

• supports peroxide neutralization via thioredoxin peroxidases

Catalase and Peroxidases

Catalase does not directly consume NADPH in its main reaction, but NADPH-dependent redox systems stabilize the broader antioxidant network that supports catalase function and peroxide management.

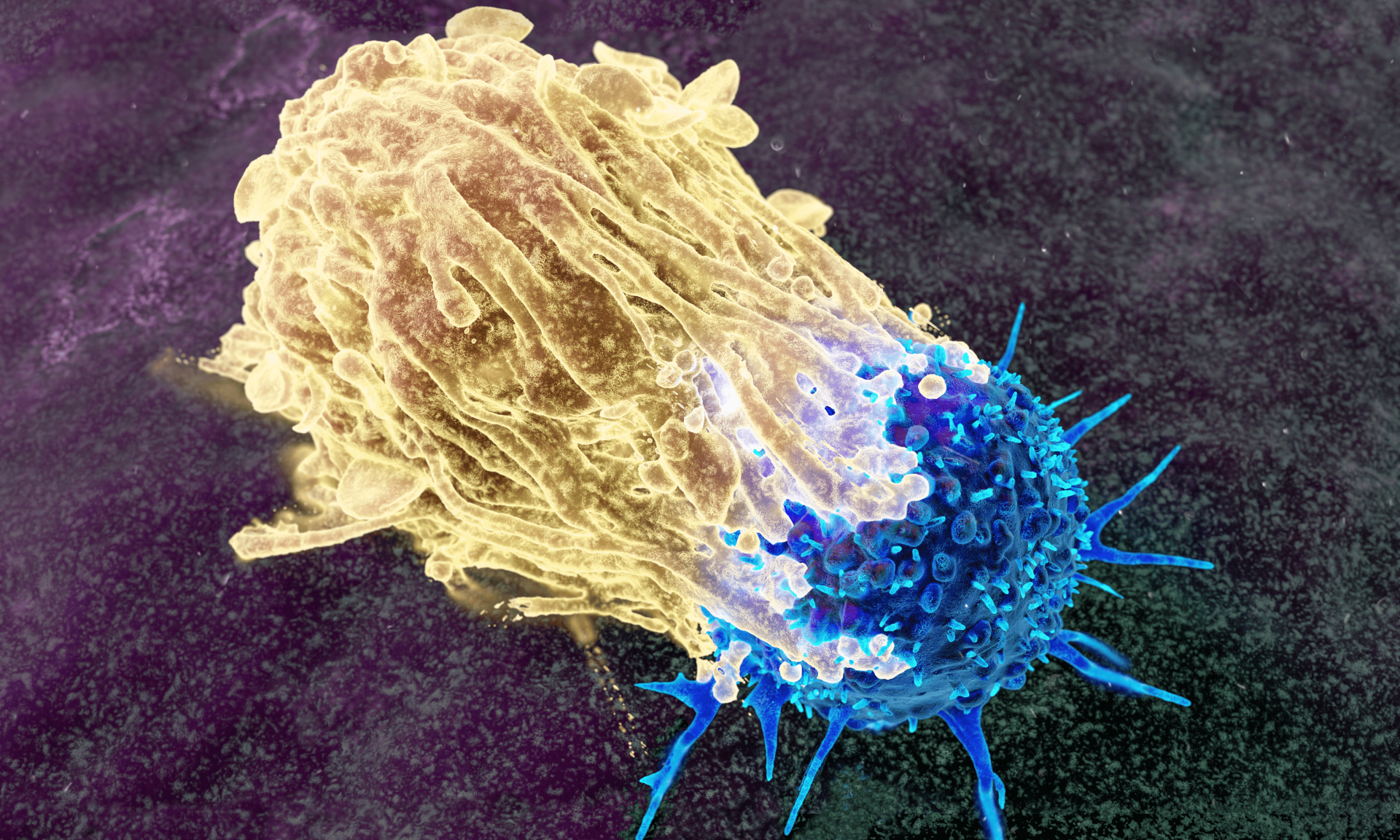

NADPH and Immune Function

NADPH Oxidase and the Respiratory Burst

In neutrophils and macrophages, NADPH is used as substrate for NADPH oxidase (NOX2) to generate superoxide inside the phagosome. This is central to antimicrobial killing and the “respiratory burst,” a dramatic increase in oxygen consumption during pathogen destruction.

Clinical relevance is highlighted by chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), where genetic defects impair NADPH oxidase activity and result in severe recurrent infections.

PPP flux becomes particularly important here because immune cells require rapid NADPH generation to sustain oxidant production during prolonged responses.

Nitric Oxide Synthesis

All three nitric oxide synthase isoforms (nNOS, eNOS, iNOS) require NADPH as an electron donor. For endothelial function, NADPH availability (often tied to G6PD activity) can influence NO production and therefore vascular tone, blood pressure regulation, and endothelial health.

Compartmentalization: NADPH Is Not One Pool

NADPH is compartmentalized and does not freely diffuse across membranes. Each compartment maintains distinct pools:

Cytosolic NADPH

Generated mainly by:

• oxidative PPP

• ME1

• IDH1

Supports:

• lipid/cholesterol synthesis

• nucleotide production

• cytosolic antioxidant systems

Mitochondrial NADPH

Generated mainly by:

• NNT

• IDH2

• mitochondrial malic enzyme (e.g., ME3)

• mitochondrial folate cycle

Supports:

• defence against mitochondrial ROS

• mitochondrial biosynthetic needs

This compartmentalization matters clinically because disturbances in one pool may not be “rescued” easily by another.

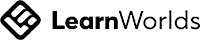

NADPH in Cancer Metabolism

Cancer cells often require elevated NADPH for two major reasons:

1. nucleotide synthesis (for rapid proliferation)

2. ROS defence (against oxidative stress generated by accelerated metabolism)

Mechanisms Cancer Uses to Elevate NADPH

Common strategies include:

• AKT–NADK axis increasing NADP⁺ availability

• Upregulated G6PD and malic enzymes, particularly with mutant p53 contexts

• Calmodulin activation of NADK

• Altered one-carbon metabolism contributing to NADPH pools

• IDH1/2 mutations, which can consume NADPH and create unique dependencies

Therapeutic Implications

NADPH dependency is a potential vulnerability. Preclinical strategies include targeting:

• G6PD

• NADK

• ME1

• NAD⁺ salvage pathways (e.g., NAMPT), especially in contexts such as NAPRT deficiency

The challenge remains specificity: targeting cancer NADPH metabolism without excessive toxicity to normal tissue demands careful pathway selection and context-aware treatment logic.

Clinical Significance: G6PD Deficiency

G6PD deficiency is the most common human enzyme deficiency, affecting hundreds of millions globally. Red blood cells rely on PPP as their primary NADPH source. Without adequate NADPH, they cannot maintain reduced glutathione, making them vulnerable to oxidative damage.

Key Clinical Features

Oxidative triggers can precipitate hemolysis:

• certain medications (e.g., some antimalarials, sulfonamides)

• infections

• fava beans

Beyond Hemolysis: Immune Vulnerability in Severe Cases

More severe G6PD variants can reduce NADPH oxidase capacity in neutrophils, leading to impaired respiratory burst function and recurrent infections—an immune phenotype that can resemble CGD.

NADPH in Diabetes and Metabolic Disease

NADPH plays complex, sometimes paradoxical roles in diabetes.

Insulin Resistance and Secretion

Disruption of mitochondrial NADP⁺/NADPH balance can influence insulin signalling and glucose metabolism. In β-cells, PPP-derived NADPH supports glucose-stimulated insulin secretion.

Polyol Pathway

Hyperglycaemia can drive the polyol pathway, consuming NADPH via aldose reductase. This can reduce antioxidant capacity by limiting glutathione regeneration, contributing to oxidative stress and diabetic complications.

Hyperglycaemia and NOX Activation

Hyperglycaemia can also activate NOX, increasing ROS production and NADPH consumption—sometimes driving compensatory PPP flux. The result can become a self-reinforcing pathological cycle.

NADPH in Aging, Longevity, and Neurodegeneration

Aging and Cellular Senescence

NOX enzymes contribute to oxidative stress and senescence pathways. Angiotensin II–related NOX activation can drive ROS-mediated signalling that impacts mitochondrial function and pro-senescent inflammatory programs.

Neurodegenerative Disease

NADPH oxidase activity is implicated in oxidative damage across multiple neurodegenerative conditions. In experimental models, NOX inhibition has shown neuroprotective effects, though real-world translation depends on isoform specificity and preserving physiological ROS signalling.

NADPH in Exercise Physiology

Exercise-induced ROS is not universally harmful—it can act as signalling that supports glucose handling and adaptation.

NOX2-derived ROS appears necessary for normal exercise-stimulated glucose uptake and GLUT4 translocation in muscle. Training can also reduce pathological NOX hyperactivity in certain disease models, lowering systemic inflammation and improving exercise tolerance.

Measuring NADPH: From Classic Assays to Live-Cell Biosensors

NADPH measurement has evolved from bulk biochemical methods to real-time compartment tracking.

Traditional Methods

• spectrophotometric measurement at 340 nm

• enzymatic cycling assays

• mass spectrometry metabolomics

Modern Biosensors

Genetically encoded and chemigenetic sensors now allow real-time monitoring of NADPH dynamics across compartments—enabling much deeper insights into disease metabolism and therapeutic response.

Redox Homeostasis: Why Ratios Matter

Cells maintain distinct redox ratios to support different functions:

• NADPH/NADP⁺ is typically maintained high (often strongly biased toward NADPH), favouring reductive biosynthesis and antioxidant defence.

• NAD⁺/NADH is maintained high in the cytosol, favouring oxidative metabolism.

These ratios are not just biochemical trivia—they determine the direction and feasibility of entire networks of reactions.

Future Directions

NADPH biology is moving toward more precise, compartment-aware interventions:

•Compartment-specific targeting (e.g., mitochondrial vs cytosolic NADPH support)

•Personalized metabolic profiling in cancer and chronic disease

•NADPH as a biomarker, enabled by advanced sensing approaches

•Combination strategies pairing NADPH-targeted modulation with standard therapies (where appropriate)

Key Takeaway

NADPH sits at the intersection of biosynthesis, detoxification, immune defence, oxidative stress resilience, and disease metabolism. Understanding NADPH is not merely academic—it provides a unifying lens for interpreting metabolic flexibility, redox fragility, and therapeutic vulnerability across a wide range of clinical conditions.